First Nations

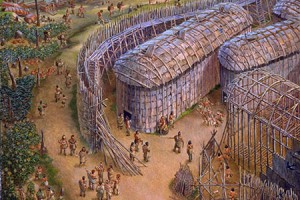

(Illustration of Teiaiagon Village. Image courtesy of the City of Toronto Heritage Department)

While there is little record of the architecture of Teiaiagon Village, accounts from French explorer, Rene-Robert Caviler in 1680, suggest there were dozens of longhouses, such as the ones shown above, that housed hundreds of people. Longhouses housed several families along female lines. The basic construction consisted of driving wooden posts into the ground and weaving flexible branches between them lashed by bark. The structures were then sheathed by elm or cedar bark. Sleeping platforms ran the length of the house while 6 – 12 hearths would line the centre of the houses with vents above to allow smoke to escape. Entrances were often covered with animal hides. Teiaiagon was burned to the ground by French and Huron forces in 1687 in retaliation for previous aggressions by the Seneca and their English allies.

Fur Traders and Coureurs de Bois:

Teiaiagon was abandoned after being burned to the ground and it was not until 1716 that the site was again home to a permanent structure. The Douville brothers constructed a trading post called Le Magasin Royal (also known as Fort Douville) believed to be near the site of the Baby Point Club where European items such as buttons, shirts, ribbons, combs, knives, looking glasses, axes, flour, lard, salt, pepper, prunes, raisins, olive oil, tobacco, vermillion, powder and shot were exchanged with trappers and aboriginal people for furs and pelts. Architecturally, Le Magasin Royal was described as ‘little more than a log cabin’ but its significance lies in it being the first non-aboriginal building in the Toronto area. The site was again abandoned in 1730 as new sites were built closer to Lake Ontario.

Pioneers and Settlers

(Baby family cottage. Photo image courtesy of the City of Toronto Archives)

Upon acquiring the land in 1820, James Baby fished and planted an apple orchard on his 114-acre property sandwiched between the small hamlets of Lambton Mills and Kings Mill. The cottage later built by his son James or his grandsons was unremarkable (pictured above in 1885, long after Baby’s death). The cottage’s precise location is not known but maps from the time show the estate near the southeast corner of the roundabout at Humbercrest Blvd. and Baby Point Rd.

20th Century Development

1.

1.  2.

2.

1. First Baby Point homes constructed in 1913, at the southwest corner of Baby Point Road and Jane Street. The stone entrance gates to the Baby Point area were constructed in 1911. (Photo image courtesy of the City of Toronto Archives)

2 .First Baby Point Club members 1923. (Photo image courtesy of the City of Toronto Archives)

When Robert Home Smith acquired the Baby estate lands from the Government of Upper Canada, who in turn purchased it from the descendants of James Baby, he did so with the intention of developing the lands into a grand residential neighbourhood. In addition to the Baby Point subdivision, Home Smith also acquired lands for the Glebe subdivision (now known as the Kingsway), the Riverside subdivision (Riverside Dr.), the Old Mill subdivision and the Bridge End subdivision (east side of the Humber River above the York Old Mill Tennis Club), all along the Humber River Valley. Angliae para Anglia procul (A bit of England far from England) was the project’s slogan, reflecting Home Smith’s architectural vision for the community. This encompassed more than just the homes with plans for a ‘noble city park and boulevard’ with the development of street planning, architecture and construction capturing the essence of England. Home Smith offered potential purchasers of land plots architectural and construction services but also gave them the option of using their own architects provided their design met with Home Smith’s approval and complied with a long list of covenants the owners agreed to for a period of 30 years. Home Smith’s vision included recreational amenities and he constructed the Old Mill Tea Garden (known today as The Old Mill), St. George’s Golf Course, tennis courts, lawn bowling greens, boat houses adjacent to the Humber River, and ultimately Sunnyside Bathing Pavilion and Amusement Park (in his capacity as Chairman of the Toronto Harbour Commission).

Land reserved by Home Smith allowed creation of the Baby Point Club in 1923 by residents of the growing neighbourhood. The Baby Point Club has helped to maintain a small community atmosphere for more than 90 years and has been the social and recreational nucleus of Baby Point with tennis courts, a lawn bowling green, a skating rink and a clubhouse which has been expanded and renovated since its original build.

Modern Day

- Baby Point Club ice rink with the Conn Smythe house in the background. To learn more about the Conn Smythe heritage-designated house at 68 Baby Point Road, please go to the Notable Residents page under the History section of this website. (Photo image courtesy of Danica Loncar)

2. Baby Point Club pumpkin parade, Halloween 2021. (Photo image courtesy of Stephen Bartolini)

In 2013, the Baby Point Heritage Foundation made application to the City of Toronto to designate the Baby Point community as a Heritage Conservation District (HCD). In 2015, the Baby Point Heritage Conservation District Study was authorized and prioritized by Toronto City Council, and City Planning initiated the project in 2017. In 2018, City Planning officially received approval to proceed from the study phase to the planning phase of the HCD. The Baby Point District HCD plan includes 180 homes throughout the Baby Point loop constructed from 1911 – 1941 that have not been materially altered as seen from the street.

The HCD designation will ensure that Home Smith’s original vision for the community will be preserved for generations. With the increasing densification of the City of Toronto, preserving the architectural heritage of one of the most historically significant neighbourhoods in Canada remains a priority of both the Baby Point Heritage Foundation and many of its residents. However, the HCD does not dictate how a homeowner can renovate, decorate or modernize their homes but it does seek to prevent the outright destruction or material modification of historic homes. The final guidelines will be announced when the application has been approved.